The Dropout • David Gee

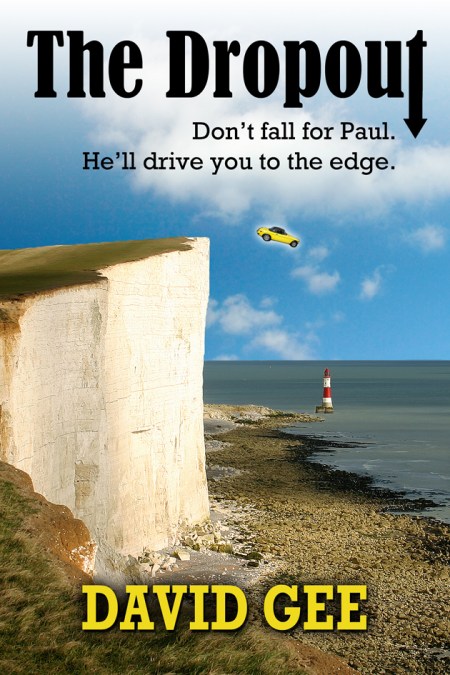

The Dropout

David Gee

307 pages • Matador • September 09, 2012 [PB]

………………………………………………………………………………………….

“I would tell her that I’d come to see myself as a destructive force, like Shiva, that I ruined the life of everyone who came near me.”

Once you label me you negate me, Kierkegaard observed. 19-year-old Paul Barrett has labelled himself a date-rapist but, in so doing, is not so much negating himself as melodramatising – as perhaps only a sexually angst-ridden teenager can. In reality, whilst his crassly fumbled, over-enthusiastic and unwelcome attempts to get laid are undoubtedly reprehensible, even indefensible, they hardly make him a monster. Far from being the sexual predator he self-indulgently portrays himself as being, the more prosaic truth seems to be that he’s just young, dumb and full of cum. Paul’s tragedy is that he finds it easier to break hearts than hymens.

Though blessed with two apparent natural advantages, looking like Ewan McGregor and being similarly well-endowed, he finds he is physically more irresistible to his college friend, Neil, than to his girlfriend, Meredith. Paul’s attempt to have full sex with Meredith, an American student on sabbatical who has taken the silver ring pledge of chastity, results in her accusing him of attempted rape. Neil kisses Paul and, when he is repulsed, throws himself to his death from the campus bell-tower. Not an auspicious start for a young man trying to pursue an academic path at ‘a Midlands University’ (a thinly-disguised Birmingham, I suspect).

Understandably depressed and chastened by these setbacks, Paul drops out of uni and makes his way home to the south coast via London, where he meets, and falls for, single mother Rachel. Rachel’s breakup with her son Simon’s bisexual dad is too raw for her to allow Paul into her bed but she is willing to allow him into her, and Simon’s, life.

Arriving back in ‘Boredom-on-Sea’, his sarcastic name for his dreary out-of-season Sussex resort hometown, Paul receives a less-than enthusiastic welcome from his disappointed parents. However, his mother, Mary, finds him work with her wealthy brother, Jack Pemberton, in his furniture factory, where it soon becomes apparent to Paul that his version of the town’s real name is a serious misnomer – Bonkdom-on-Sea would be more appropriate.

As he attempts to re-integrate into a provincial small town life he never embraced in the first place, Paul finds himself at the centre of a web of dysfunctional relationships, marital, sexual and familial, in which he becomes the naïve catalyst for dramatic, if not catastrophic, change as things spiral out of control around him. In this he can be seen as something of a Candide figure, though without l’Optimisme of the original – Boredom-on-Sea being by no stretch of the imagination a Panglossian best of all possible worlds!

Paul may have imagined he was returning to an unremarkable provincial life, stable but dispiritingly dull. On the contrary, David Gee’s tongue-in-cheek, if dark, social and sexual satire (a sort of cross between David Lodge and Tom Sharpe) leads us through a topsy-turvy world of sexual shenanigans and unconventional relationships conducted behind the outwardly respectable façade of small town life, a façade which the return of the prodigal son cracks wide open, to reveal the unsavoury secrets lurking behind it.

The hesitant attempt, and partial success, of Paul’s ex-schoolmate (and erstwhile bully), Jim, to get into his pants is touchingly shown, and Jim’s sad efforts to reconcile his own sexuality in an uncompromisingly heterosexist society (on the surface at least) is very poignant and rings entirely true. One grieves for the many lost souls like Jim who inhabit the sad, furtive, underground, half-world of gay and MSM sex to be found outside of London and other of Britain’s major cities.

Gee’s cynical and baleful view of human nature could be read as a counterblast to hypocrisy and a salutary reminder of the dire consequences of failure to live life openly and honestly, accepting that, far from being unspeakable aberrations, infidelity, bigamy, sexual-ambiguity, homo- and bi-sexuality, even incest, are all part of the fabric everyday life and should be treated as such. Gee himself has apparently enjoyed (if that’s the word) an international jet-setting lifestyle so it is possibly as a result of this that his tone is sometimes jaded and world-weary.

But if this makes The Dropout sound heavy-going and over-earnest, it is in fact, though undeniably often bleak and with a high death-count, also witty, clever, insightful and worldly-wise, with some wry (and often gallows) humour throughout. But there is redemption at the end of the saga, although I won’t give away in what form the deus ex machina eventually appears.

Indeed, Paul’s travails can perhaps best be read as a sort of quest, a pilgrimage-of-grace, through which he has to find himself and grow from a self-absorbed and self-pitying youth into a wiser and more compassionate man. This may not be a rip-roaring comedy of manners but a humane Voltairean smile of reason hovers over it nevertheless.

Gee often cleverly examines the same scene from different perspectives, sacrificing his own authorial voice the better to allow the reader to draw his own conclusions. Along the way, unfortunately, some careless proof-reading and irritating Americanisms in the text (high school, dove for dived, cell-phone, panty-hose, asshole) jar rather. (If pitched at an American readership it is hard to imagine what on earth they make of Gee’s all-too accurate representation of English provincial life in the early 21st century, or how they might relate to it.)

These minor niggles apart, this is a highly-absorbing, entertaining and ultimately satisfying read, and one which I would unhesitatingly recommend.